If you enjoy independent indie game coverage, consider supporting Indie-Games.eu on Patreon. It helps keep the site independent.

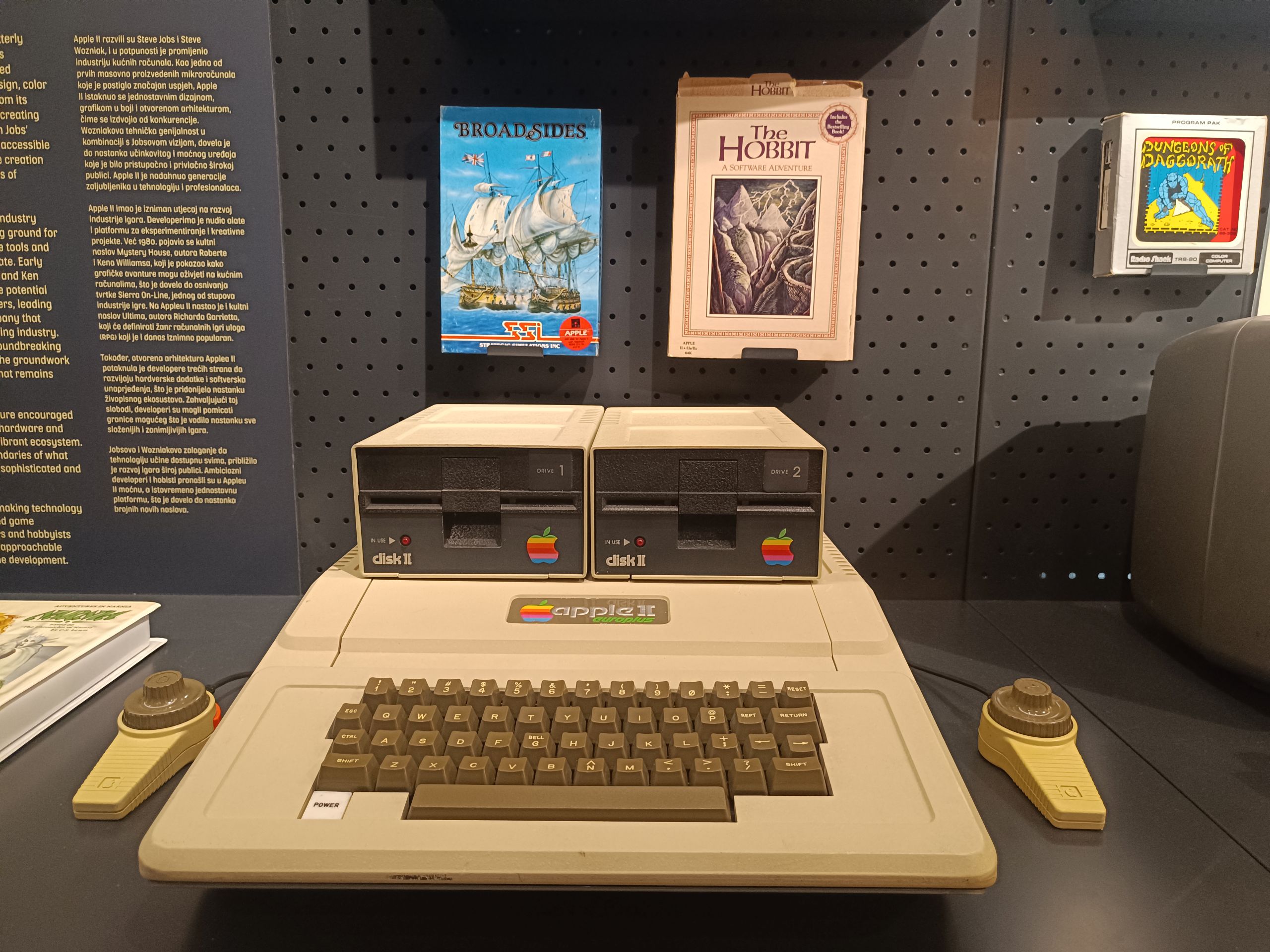

Yesterday, the panel Stories from the Past: The History of Croatian Video Games was held at Kaptol Boutique Cinema in Zagreb, as part of the opening events for an exhibition dedicated to the historical development and significance of the video game industry in Croatia. The exhibition was organized by the Video Game History Museum in Zagreb and represents the first systematic and chronological overview of Croatian gaming history. In addition, the museum has now opened a new space dedicated exclusively to Croatian video games, so if you haven’t visited the museum yet, or haven’t been there in a while, it is definitely worth stopping by again.

The panel featured Damir Muraja, a pioneer of computing and the author of the first globally successful Croatian video game; Janko Mršić-Flögel, a scientist, entrepreneur, and video game creator from the 1980s; Admir Elezović, art director at Croteam, the most renowned Croatian game development studio; and Damir Šlogar, founder of the Video Game History Museum and the author of numerous internationally acclaimed games. The program was moderated by Ante Vrdelja, a video game industry veteran with more than three decades of experience.

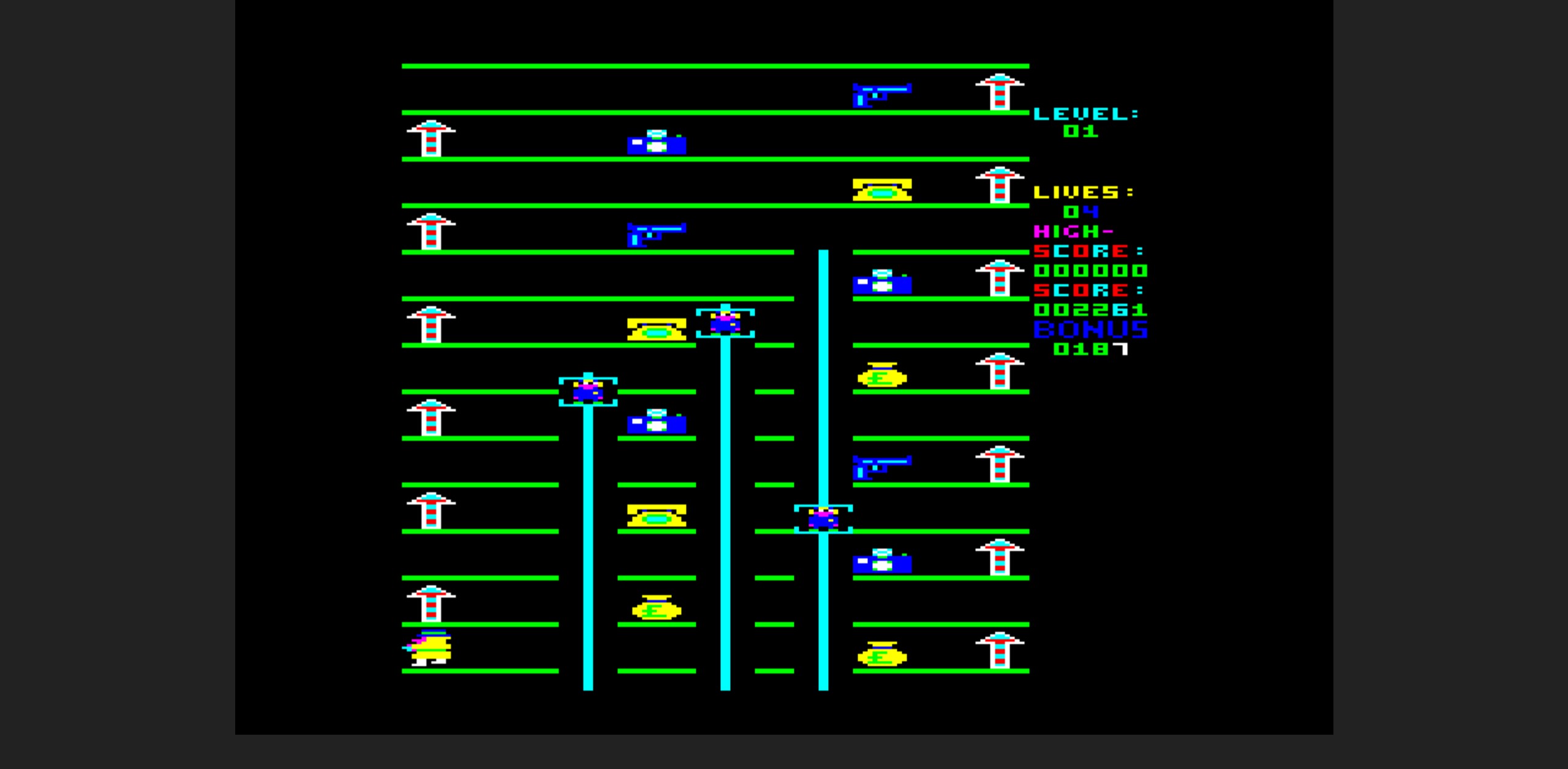

Before the panel began, museum curator Šlogar presented a retrospective of the history of Croatian video games. According to him, video game development in Croatia began as early as the early 1980s, under conditions of limited access to technology and strict bans on importing computers. Despite this, some of the first commercially released video games with international success were created in Croatia. The year 1984 is considered a turning point, marked by the release of Kung Fu by Damir Muraja, as well as the first games by Janko Mršić-Flögel and other authors. A key role in the development of the scene was also played by the Multimedia Center led by Branimir Makanec, which provided many people with their first contact with computers and programming.

By the mid-1980s, Zagreb saw the emergence of the first magazine dedicated exclusively to video games, Pilot Video, the first domestic publisher Suzy Soft, and a range of media covering gaming culture, further confirming that Croatia became a regional pioneer at a very early stage. In the 1990s, the domestic scene entered the global market, with the most famous example being Croteam and the Serious Sam franchise.

The panel quickly touched on the challenges of acquiring technology in Yugoslavia at the time. Muraja openly admitted: “I bought my computer in Munich and smuggled it in, like most people back then. It simply wasn’t possible to buy one here. It exceeded the allowed quota, you had to find a freight forwarder and pay a whole range of costs.” Other panelists shared similar experiences, from faulty ZX Spectrums and Apple IIs purchased in Zagreb to the first computers brought from abroad, often without a single game, which pushed many to start programming themselves.

One of the central topics was the long-standing debate about which game should be considered the first Croatian video game. Šlogar emphasized the complexity of the question: “The answer is extremely complex. We looked at a combination of criteria, whether the game was created in Croatia, whether the authors were Croatian, and whether it had international distribution.” He explained that there was no clear release date system as we know it today: “A game would appear in one shop on two cassette tapes. If it sold well, more would appear.” As a result, based on available data, Kung Fu is still considered the first Croatian game with international commercial distribution, even though other domestic games were released the same year.

Of course, several other titles were mentioned as well, such as Nifty Lifty for the BBC Micro from 1984, also authored by Mršić-Flögel. However, it was noted that some earlier games had even been released on foreign markets, but without significant commercial success. It is believed that the first domestic video game was created by the late Branko Špoljarić, but it simply did not reach the level of popularity achieved by Kung Fu.

Muraja pointed out that game development did not begin with commercial ambitions: “We didn’t write games to make money. We wrote them for ourselves, because there were no games. If you wanted to play, you had to write them yourself.” According to him, that necessity laid the foundation of the domestic scene: “That mechanism of writing our own games is the reason and the basis that led us to all of this.” He added that Croatia had a specific mindset suited to such development: “A nation that writes games has to be inclined toward improvisation. We had to invent everything ourselves. We struggled with the lack of understanding from our surroundings, even from our own families. But when the first checks arrived, everything changed.”

The Multimedia Center played a major role in connecting early programmers, which Muraja described as a key gathering point: “We exchanged information, books, magazines. You couldn’t go to a library and borrow a book, you had to get it from abroad or copy it.” According to him, this openness was crucial: “Everything I knew, I shared with others. Today, code is hidden and patented, but back then that wouldn’t even cross our minds.”

When asked about relationships among developers, Elezović recalled a strong sense of community: “People exchanged code, music, graphics. Copy parties were also important for exchanging ideas, and they were held even during the Homeland War. There was no Indian guy on YouTube making a tutorial for you back then, we all shared everything with each other, whereas today every developer guards their code.” Speaking from Croteam’s perspective, Elezović concluded: “We first wanted to make games that we ourselves would play. That’s how it started, with football games and then Serious Sam. Only when it started becoming a business did we realize it was something worthwhile. We contributed to putting Croatia on the gaming map. We’re glad that today’s development teams still remember that and draw inspiration from our games.”

The participants also spoke in detail about realistic sales figures and market conditions in the early days of the industry. As Muraja pointed out, expectations back then were far more modest than today: “It was fine for us if, say, four to five thousand copies were sold. Generally, that was already very good.” Games were distributed on cassette tapes and sold in the thousands, mostly for the Commodore 64, and Muraja also recalled collaborations with foreign publishers: “For Paradox, we sold games for Mirrorsoft or Interceptor Software. It all went on cassette tapes and sold in thousands of copies.”

Although some games reached impressive numbers, piracy was widespread. “I wouldn’t say it went over ten thousand, but we know there were pirate operations in Belgium where they copied games and produced cassettes,” said Mršić-Flögel, describing how software was sometimes copied even within official production facilities. Despite everything, the market was huge, especially considering the popularity of the ZX Spectrum: “Altogether, around five million ZX Spectrum computers were sold. That’s very important, because the relatively low price brought microcomputers into households.”

“We lived in a world of piracy,” Muraja said candidly. “Newspapers openly sold cassette tapes with 200 of the latest games, and nobody paid attention to it, especially in Yugoslavia.” He added that copyright was barely considered at all: “There wasn’t even a sense that foreign copyrights needed special protection.”

From the perspective of today’s industry, Elezović drew parallels between past and present challenges: “The good side of the industry today is that you can sit in an armchair and make a game that becomes a huge hit.” At the same time, he warned about negative trends: “We have megalomaniacal projects, games nobody plays, similar to films nobody watches.” Elezović believes the industry is currently in a kind of transitional phase: “The golden age isn’t over. Maybe we’re in a silver phase now, but I’m sure that in the next ten years a world-class title will come out of Croatia.”

The panel concluded with reflections on the development of the industry and creativity. Muraja explained why he stepped away from game development: “I left programming when it became a bureaucratic thing.” He added that developers once had complete control over the computer: “On the Spectrum, nothing else was running except your game.” Today, he believes, things are coming full circle again: “Big productions have narrowed into a tight space, and at the bottom a space has opened up for new, young authors and completely different kinds of games.”

In closing, he sent a message to everyone considering game development: “The idea is important, but the key concept is addictiveness. If a colleague wants to keep playing after testing—then you’re on the right track.” He concluded very pragmatically: “Writing code is the smaller part of the job. The main job is debugging.”